Elizabeth St sits above Williams Creek, formerly known as River Townsend, a seasonal river which frequently flooded in the early colonial years of Melbourne. Today this mighty torrent is contained in a drain below the street. But this waterway has a lot to tell us about disasters, flood management, and the colonial past and present of Melbourne.

How much of urban life is invisibilised, buried beneath the pavement? This walk will take you on a journey from Bouverie Creek on the University of Melbourne campus to the meeting place of the Williams Creek and the Birrarung (Yarra River) near Flinders St Station.

Along the way, we stop at places of burial and erasure in the urban fabric, to ask what happens when projects of urbanisation and colonisation succeed – or fail. You will find opportunities to reflect on flood management, vulnerability, social capital, urban infrastructure, "natural" disasters, and the centrality of Wurundjeri Country.

Follow the stops listed on the map and refer to the audio guide provided in the learning resources. Each stop along the way has a short audio history along with additional written and visual resources. You can play and pause the podcast as you go – take as much time as you need. Don't forget to take your own fieldnotes and refer to the reflection prompts.

Location

Carlton to Birrarung (Yarra) River. This walk begins at Melbourne University and ends at the Main Drain, Flinders Street Station. Key sites along the way include the Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener memorial and Queen Victoria Market.

Access the directions and key locations on Google Maps here.

Accessibility

This walk is on paved footpaths and involves minimal road crossings. The audio guide has been designed to be listened to either while walking on foot or while taking the tram down Elizabeth St. It is possible to take the tram from Haymarket or Queen Victoria Market down Elizabeth St, to avoid the majority of walking. Haymarket, Queen Victoria Market, and Flinders Street tram stops on Elizabeth St are wheelchair accessible. However, please note that the footpath down Elizabeth St is uneven and is not always appropriate for wheelchair access. Guide dogs and assistance animals are welcome across all areas this walk.

Buried waterways has been designed to listen to en route, with headphones on a personal mobile device, with prompts for pause and reflection at each stop. This experience can also be modified to be listened to at home, using Google street view and provided photos to prompt reflection. Maps, directions, photos, and access notes are included. Please be aware of your surroundings and adhere to road safety guidelines at all times.

Distance

4km one way, approx. 1 hour walk.

Listen

Embed walking tour audio here.

Transcription

Embed audio guide transcription here.

Authors: Willow Ross and Ilan Wiesel

With thanks to: Mandy Nicholson, Gyorgy Scrinis, Guy Johnson, and Joseph Toscano

Introduction

References:

Smith, Neil. “There’s No Such Thing as a Natural Disaster.” Blog. Items: Insights from the Social Sciences (blog), 2006. https://items.ssrc.org/understanding-katrina/theres-no-such-thing-as-a-natural-disaster/.

Stop 1 - Bouverie Creek

References:

Greenaway, Jefa, and Samantha Comte. The Water Story — A conversation between Jefa Greenaway and Samantha Comte. Transcript, July 6, 2019. https://art-museum.unimelb.edu.au/resources/articles/the-water-story-a-conversation-between-jefa-greenaway-and-samantha-comte/.

Hope, Zach. “One Eel of a Story: The Slippery Truth of a Fishy Underground Migration.” The Age, February 6, 2021, 6th February 2021 edition, sec. Victoria. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/one-eel-of-a-story-the-slippery-truth-of-a-fishy-underground-migration-20210122-p56w2z.html.

Kimber, Julie, Peter Love, and Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, eds. The Time of Their Lives: The Eight Hour Day and Working Life. Albert Park, Vic.: Australian Society for the Study of Labour History - Melbourne, 2007.

Thomas, Georgia. “The Living Pavilion Celebrates Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainability.” Green Magazine, May 1, 2019. https://greenmagazine.com.au/the-living-pavilion-indigenous-knowledge-sustainability/.

Stop 2 - Lincoln Square

References:

Harris, Cecilia. “An Indigenous-Led Approach to Urban Water Design.” Australian Water Association, May 21, 2024. https://www.awa.asn.au/resources/latest-news/community/engagement/indigenous-led-approach-urban-water-design.

Little, Richard G. “Managing the Risk of Cascading Failure in Complex Urban Infrastructures.” In Disrupted Cities. Routledge, 2009.

Moran, Uncle Charles, Uncle Greg Harrington, and Norm Sheehan. “On Country Learning.” Design and Culture, January 2, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17547075.2018.1430996.

Pfleiderer, Ralf. “Flood Purge and SWH at Lincoln Squares Project.” Council Report. Melbourne: Storm Engineering, May 2017.

Stop 3 - Park Hotel Prison

References:

Arroyo, Laura. “Park Hotel Empty as 26 Refugees Are Released, Morrison Government Refuses to Release Remaining 6.” Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (blog), April 7, 2022. https://asrc.org.au/2022/04/07/park-hotel-empty-as-26-refugees-are-released/.

Bolin, Bob, and Liza C. Kurtz. “Race, Class, Ethnicity, and Disaster Vulnerability.” In Handbook of Disaster Research, edited by Havidán Rodríguez, William Donner, and Joseph E. Trainor, 181–203. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63254-4_10.

Australian Associated Press. “Final Detainees at Melbourne’s Park Hotel Freed as Refugee Releases Continue in Lead-up to Election.” The Guardian, April 7, 2022, sec. Australia news. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/apr/07/final-detainees-at-melbournes-park-hotel-freed-as-refugee-releases-continue-in-lead-up-to-election.

Osborne, Zoe. “Beyond the Park Hotel: Australia’s Immigration Detention Network.” Al Jazeera. Accessed May 23, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/13/beyond-the-park-hotel-australias-immigration-detention-network.

Stop 4 - University Square

References:

Grant, Jill. “The Dark Side of the Grid: Power and Urban Design.” Planning Perspectives, January 1, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665430152469575.

Blatman-Thomas, Naama, and Libby Porter. “Placing Property: Theorizing the Urban from Settler Colonial Cities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43, no. 1 (2019): 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12666.

Rizzetti, Janine. “The Elizabeth Street Creek.” Blog. The Resident Judge of Port Phillip (blog), April 6, 2009. https://residentjudge.com/2009/04/06/the-elizabeth-street-creek/.

Annear, Robyn. Bearbrass: Imagining Early Melbourne. Melbourne: Black Inc., 2014. https://www.blackincbooks.com.au/books/bearbrass.

Stop 5 - Haymarket

References:

Grant, Jill. “The Dark Side of the Grid: Power and Urban Design.” Planning Perspectives, January 1, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665430152469575.

Blatman-Thomas, Naama, and Libby Porter. “Placing Property: Theorizing the Urban from Settler Colonial Cities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43, no. 1 (2019): 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12666.

Rizzetti, Janine. “The Elizabeth Street Creek.” Blog. The Resident Judge of Port Phillip (blog), April 6, 2009. https://residentjudge.com/2009/04/06/the-elizabeth-street-creek/.

Annear, Robyn. Bearbrass: Imagining Early Melbourne. Melbourne: Black Inc., 2014. https://www.blackincbooks.com.au/books/bearbrass.

Stop 6 - Common Ground

References:

New York City. “Common Ground | Breaking Ground,” 2024. https://breakingground.org/

Power, Emma R, Ilan Wiesel, Emma Mitchell, and Kathleen J Mee. “Shadow Care Infrastructures: Sustaining Life in Post-Welfare Cities.” Progress in Human Geography 46, no. 5 (October 1, 2022): 1165–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325221109837.

Johnson, Guy. Common Ground: Past and Future. Zoom Interview, May 28, 2024.

Launch Housing, “Elizabeth Street Common Ground.” Accessed May 28, 2024. https://www.launchhousing.org.au/service/elizabeth-street-common-ground.

Stop 7 - Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener Memorial

References:

Balla, Paola. Executed in Franklin Street - City of Melbourne. November 26, 2015. Art Exhibition. http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/arts-and-culture/city-gallery/exhibition-archive/Pages/executed-in-franklin-street.aspx.

Clements, Nicholas. The Black War: Fear, Sex and Resistance in Tasmania. St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 2014.

Eidelson, Meyer. Melbourne Dreaming: A Guide to the Aboriginal Places of Melbourne. Canberra : Victoria: Aboriginal Studies Press ; Aboriginal Affairs, 1997.

Pybus, Cassandra. Truganini: Journey through the Apocalypse. Sydney, N.S.W: Allen & Unwin, 2020.

Spearim, Boe. “Frontier War Stories.” Frontier War Stories. Accessed March 1, 2022. https://awesomeblack.org/shows/frontier-war-stories/.

Toscano, Joseph. Lest We Forget: The Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener Saga. Melbourne: Anarchist Media Institute, 2008.

Stop 8 - Queen Victoria Market

References:

Cole, Colin E. Melbourne Markets, 1841-1979 : The Story of the Fruit and Vegetable Markets in the City of Melbourne / Edited by Colin E. Cole. Footscray, Vic: Melbourne Wholesale Fruit and Vegetable Market Trust, 1980.

Morgan, Marjorie Jean. The Old Melbourne Cemetery, 1837-1922. Australian Institute of Genealogical Studies, 1982.

Murphy, Maureen, Rachel Carey, and Leila Alexandra. “The Resilience of Melbourne’s Food System to Climate and Pandemic Shocks.” University of Melbourne, 2022. https://doi.org/10.46580/124370.

Scrinis, Gyorgy. Queen Vic Market & Melbourne’s Food Security. Zoom Interview, May 22, 2024.

Razak, Ishkhandar. “Every Day, Thousands of People Walk over a Burial Ground at One of Melbourne’s Biggest Tourist Attractions.” ABC News, July 23, 2023. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-07-24/queen-vic-market-cemetery-burial-ground-development-lendlease/102624880.

Swift, Neil., and Edmund Finn, eds. The Chronicles of Early Melbourne 1835-1852, Historical, Anecdotal and Personal, by “Garryowen.” Melbourne: Fregusson and Mitchell, 1964.

Stop 9 - Williams Creek Crossing

References:

Swift, Neil., and Edmund Finn, eds. The Chronicles of Early Melbourne 1835-1852, Historical, Anecdotal and Personal, by “Garryowen.” Melbourne: Fregusson and Mitchell, 1964.

Gary Presland (2014) The place for a village: how nature has shaped the city of Melbourne. Museum of Victoria https://booko.info/works/2904818.

Matthews, Sarah. “The Riotous Williams.” Ask a Librarian. State Library of Victoria, 2020. https://blogs.slv.vic.gov.au/our-stories/ask-a-librarian/the-riotous-williams/.

May, Andrew. Melbourne Street Life: The Itinerary of Our Days. Kew, Vic: Australian Scholarly/Arcadia and Museum Victoria, 1998.

Stop 10 - Lake Cashmore

References:

Swift, Neil., and Edmund Finn, eds. The Chronicles of Early Melbourne 1835-1852, Historical, Anecdotal and Personal, by “Garryowen.” Melbourne: Fregusson and Mitchell, 1964.

May, Andrew. Melbourne Street Life: The Itinerary of Our Days. Kew, Vic: Australian Scholarly/Arcadia and Museum Victoria, 1998.

White, Sally, and Staff Writers. “From the Archives, 1972: Chaos as Floods Batter Melbourne.” The Age, February 14, 2020, sec. Victoria. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/from-the-archives-1972-chaos-as-floods-batter-melbourne-20200213-p540oi.html.

Stop 11 - The Main Drain

References:

Anonymous. “Anyone Know about This Tunnel under Flinders St?” Reddit Post. R/Melbourne, October 14, 2022. www.reddit.com/r/melbourne/comments/y3i95d/anyone_know_about_this_tunnel_under_flinders_st/.

Dole Army on ACA Pt1. A Current Affair. Melbourne, 2011.

McGaw, Janet, and Cliff Chang. “Melbourne’s Hidden Waterways: Revealing Williams Creek.” Double Dialogues, Summer 2010. https://doubledialogues.com/article/melbournes-hidden-waterways-revealing-williams-creek/.

Moran, Uncle Charles, Uncle Greg Harrington, and Norm Sheehan. “On Country Learning.” Design and Culture, January 2, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17547075.2018.1430996.

Otto, Kristin. Yarra: The History of Melbourne’s Murky River. Text Publishing, 2011.

Presland, Gary. The Place for a Village: How Nature Has Shaped the City of Melbourne. Melbourne: Museums Victoria, 2009.

Sparrow, Jeff, and Jill Sparrow. ‘22. Melbourne underground’ in Radical Melbourne 2: The Enemy Within. Vulgar Press, 2004.

Westgarth, William. Personal Recollections of Early Melbourne and Victoria. Melbourne: Aeterna, 2023. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5789.

Bibliography:

Annear, Robyn. Bearbrass: Imagining Early Melbourne. Melbourne: Black Inc., 2014. https://www.blackincbooks.com.au/books/bearbrass.

Anonymous. “Anyone Know about This Tunnel under Flinders St?” Reddit Post. R/Melbourne, October 14, 2022. www.reddit.com/r/melbourne/comments/y3i95d/anyone_know_about_this_tunnel_under_flinders_st/.

Arroyo, Laura. “Park Hotel Empty as 26 Refugees Are Released, Morrison Government Refuses to Release Remaining 6.” Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (blog), April 7, 2022. https://asrc.org.au/2022/04/07/park-hotel-empty-as-26-refugees-are-released/.

Balla, Paola. Executed in Franklin Street - City of Melbourne. November 26, 2015. Art Exhibition. http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/arts-and-culture/city-gallery/exhibition-archive/Pages/executed-in-franklin-street.aspx.

Blatman-Thomas, Naama, and Libby Porter. “Placing Property: Theorizing the Urban from Settler Colonial Cities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43, no. 1 (2019): 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12666.

Bolin, Bob, and Liza C. Kurtz. “Race, Class, Ethnicity, and Disaster Vulnerability.” In Handbook of Disaster Research, edited by Havidán Rodríguez, William Donner, and Joseph E. Trainor, 181–203. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63254-4_10.

City of Melbourne. “University Square – Creating a 21st Century Park.” Accessed May 28, 2024. http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/community/parks-open-spaces/park-projects-developments/Pages/reimagining-university-square.aspx.

Clements, Nicholas. The Black War: Fear, Sex and Resistance in Tasmania. St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 2014.

Cole, Colin E. Melbourne Markets, 1841-1979 : The Story of the Fruit and Vegetable Markets in the City of Melbourne / Edited by Colin E. Cole. Footscray, Vic: Melbourne Wholesale Fruit and Vegetable Market Trust, 1980.

Dangerfield, Andy. “The Lost Rivers That Lie beneath London.” BBC News, October 4, 2015, sec. London. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-29551351.

Dole Army on ACA Pt1. A Current Affair. Melbourne, 2011.

Eidelson, Meyer. Melbourne Dreaming: A Guide to the Aboriginal Places of Melbourne. Canberra : Victoria: Aboriginal Studies Press ; Aboriginal Affairs, 1997.

Grant, Jill. “The Dark Side of the Grid: Power and Urban Design.” Planning Perspectives, January 1, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665430152469575.

Greenaway, Jefa, and Samantha Comte. The Water Story — A conversation between Jefa Greenaway and Samantha Comte. Transcript, July 6, 2019. https://art-museum.unimelb.edu.au/resources/articles/the-water-story-a-conversation-between-jefa-greenaway-and-samantha-comte/.

Harris, Cecilia. “An Indigenous-Led Approach to Urban Water Design.” Australian Water Association, May 21, 2024. https://www.awa.asn.au/resources/latest-news/community/engagement/indigenous-led-approach-urban-water-design.

Hope, Zach. “One Eel of a Story: The Slippery Truth of a Fishy Underground Migration.” The Age, February 6, 2021, 6th February 2021 edition, sec. Victoria. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/one-eel-of-a-story-the-slippery-truth-of-a-fishy-underground-migration-20210122-p56w2z.html.

Johnson, Guy. Common Ground: Past and Future. Zoom Interview, May 28, 2024.

Kimber, Julie, Peter Love, and Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, eds. The Time of Their Lives: The Eight Hour Day and Working Life. Albert Park, Vic.: Australian Society for the Study of Labour History - Melbourne, 2007.

Launch Housing. “Elizabeth Street Common Ground.” Launch Housing. Accessed May 28, 2024. https://www.launchhousing.org.au/service/elizabeth-street-common-ground.

Little, Richard G. “Managing the Risk of Cascading Failure in Complex Urban Infrastructures.” In Disrupted Cities. Routledge, 2009.

Matthews, Sarah. “The Riotous Williams.” Ask a Librarian. State Library of Victoria, 2020. https://blogs.slv.vic.gov.au/our-stories/ask-a-librarian/the-riotous-williams/.

May, Andrew. Melbourne Street Life: The Itinerary of Our Days. Kew, Vic: Australian Scholarly/Arcadia and Museum Victoria, 1998.

McGaw, Janet, and Cliff Chang. “Melbourne’s Hidden Waterways: Revealing Williams Creek.” Double Dialogues, Summer 2010. https://doubledialogues.com/article/melbournes-hidden-waterways-revealing-williams-creek/.

Moran, Uncle Charles, Uncle Greg Harrington, and Norm Sheehan. “On Country Learning.” Design and Culture, January 2, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17547075.2018.1430996.

Morgan, Marjorie Jean. The Old Melbourne Cemetery, 1837-1922. Australian Institute of Genealogical Studies, 1982.

Murphy, Maureen, Rachel Carey, and Leila Alexandra. “The Resilience of Melbourne’s Food System to Climate and Pandemic Shocks.” University of Melbourne, 2022. https://doi.org/10.46580/124370.

New York City. “Common Ground | Breaking Ground,” May 2024. https://breakingground.org

Osborne, Zoe. “Beyond the Park Hotel: Australia’s Immigration Detention Network.” Al Jazeera. Accessed May 23, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/13/beyond-the-park-hotel-australias-immigration-detention-network.

Otto, Kristin. Yarra: The History of Melbourne’s Murky River. Text Publishing, 2011.

Pfleiderer, Ralf. “Flood Purge and SWH at Lincoln Squares Project.” Council Report. Melbourne: Storm Engineering, May 2017.

Power, Emma R, Ilan Wiesel, Emma Mitchell, and Kathleen J Mee. “Shadow Care Infrastructures: Sustaining Life in Post-Welfare Cities.” Progress in Human Geography 46, no. 5 (October 1, 2022): 1165–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325221109837.

Presland, Gary. The Place for a Village: How Nature Has Shaped the City of Melbourne. Melbourne: Museums Victoria, 2009.

Press, Australian Associated. “Final Detainees at Melbourne’s Park Hotel Freed as Refugee Releases Continue in Lead-up to Election.” The Guardian, April 7, 2022, sec. Australia news. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/apr/07/final-detainees-at-melbournes-park-hotel-freed-as-refugee-releases-continue-in-lead-up-to-election.

Pybus, Cassandra. Truganini: Journey through the Apocalypse. Sydney, N.S.W: Allen & Unwin, 2020.

Razak, Ishkhandar. “Every Day, Thousands of People Walk over a Burial Ground at One of Melbourne’s Biggest Tourist Attractions.” ABC News, July 23, 2023. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-07-24/queen-vic-market-cemetery-burial-ground-development-lendlease/102624880.

Rizzetti, Janine. “The Elizabeth Street Creek.” Blog. The Resident Judge of Port Phillip (blog), April 6, 2009. https://residentjudge.com/2009/04/06/the-elizabeth-street-creek/.

Scrinis, Gyorgy. Queen Vic Market & Melbourne’s Food Security. Zoom Interview, May 22, 2024.

Smith, Neil. “There’s No Such Thing as a Natural Disaster.” Blog. Items: Insights from the Social Sciences (blog), 2006. https://items.ssrc.org/understanding-katrina/theres-no-such-thing-as-a-natural-disaster/.

Spearim, Boe. “Frontier War Stories.” Frontier War Stories. Accessed March 1, 2022. https://awesomeblack.org/shows/frontier-war-stories/.

Swift, Neil., and Edmund Finn, eds. The Chronicles of Early Melbourne 1835-1852, Historical, Anecdotal and Personal, by “Garryowen.” Melbourne: Fregusson and Mitchell, 1964.

Thomas, Georgia. “The Living Pavilion Celebrates Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainability.” Green Magazine, May 1, 2019. https://greenmagazine.com.au/the-living-pavilion-indigenous-knowledge-sustainability/.

Toscano, Joseph. Lest We Forget: The Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener Saga. Melbourne: Anarchist Media Institute, 2008.

Westgarth, William. Personal Recollections of Early Melbourne and Victoria. Melbourne: Aeterna, 2023. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5789.

White, Sally, and Staff Writers. “From the Archives, 1972: Chaos as Floods Batter Melbourne.” The Age, February 14, 2020, sec. Victoria. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/from-the-archives-1972-chaos-as-floods-batter-melbourne-20200213-p540oi.html.

Walking Tour Script

Introduction (Ilan and Willow)

Intro

1972, The Age newspaper screams a bold headline: Chaos as floods batter Melbourne. Elizabeth St is awash with four feet of water as whitecaps carry away cars and sweep unlucky shoppers off their feet. A middle-aged woman is pulled to safety after she had fallen into deep water at a spot where a drain cover had been washed away, revealing a deep and fast-flowing underground river. This is not the first or last time that Melbourne’s residents of meet the Williams Creek.

This walking tour takes us on a route from the present-day campus of Melbourne University along the Bouverie and Williams Creeks, reimagining the waterscapes of this city today and in the 1800s. Once host to infamous seasonal waterways, our city now features a slew of subterranean drains that carry historic creeks – and which frequently flood. By following these waterways, we cast our minds back hundreds of years – and learn something different about Melbourne’s urban fabric today.

How much of the colonial past lives on in our climate-changed present? How does society in the city of Melbourne grapple with infrastructure and history? And how do we work to recognise these needs here and now, even as we prepare for future change?

I’m Willow Ross, and I’m Ilan Wiesel, and we are your hosts for this walking tour. We’ll hear about the 1972 Elizabeth St floods again, and along the way we’ll be joined by a series of guests to help us out.

Acknowledgement

But before we begin, we need to talk about Country. These lands, these waterways, upon which we walk this tour, always have been and always will be Wurundjeri Country. We are honoured to be guests on this Country, and we take this responsibility seriously. This tour offers an opportunity to tell stories about how the land that we call Melbourne has been invaded, occupied, and modified by British settlers – and how the First Peoples resisted.

We pay our respects to Wurundjeri Elders past and present, and to any Wurundjeri people listening. Sovereignty and custodianship over these lands, stretching back over tens of thousands of years, has never been ceded.

Three themes

This tour was made as a teaching tool for the Melbourne University subject The Disaster Resilient City. It links to three themes covered so far this semester: urban environments, urban societies, and urban infrastructures. We imagine cities as human-made environments, but in reality they are shaped by forces beyond our control. We build infrastructures to protect ourselves from hazards, then allow ourselves to get into more danger as a result. Similarly, our experiences as urban citizens are shaped by forces that bring us together and push us apart, making some more vulnerable than others.

Disasters are experienced at the pointy end of these factors. As Smith (2006) reminds us, there is no such thing as a natural disaster. But how did the planning disasters of Melbourne come to feel so natural? Follow us to find out.

References:

Smith, Neil. “There’s No Such Thing as a Natural Disaster.” Blog. Items: Insights from the Social Sciences (blog), 2006. https://items.ssrc.org/understanding-katrina/theres-no-such-thing-as-a-natural-disaster/.

1. Bouverie Creek (Willow)

Location: Intersection of Bouverie and Grattan Streets, near the 1888 Building

Pre-invasion landscapes

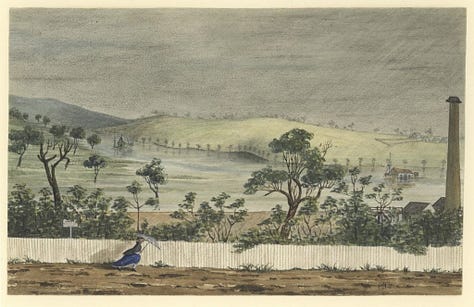

You are standing on the ancient path of the Bouverie Creek. Old colonial maps of Melbourne tell us that this street used to be known as Bouverie Creek: a seasonal waterway that ran on the downward slope from the present-day site of Melbourne University to Haymarket.

We imagine our city as a human made environment, but really it’s part of Country, it’s nature, it’s whatever you want to call it.

Look down. Look around you. What evidence can you see of waterways, floods, Country? We know that the Parkville campus is located on the lands of the Kulin Nation. This is Wurunjderi Country: unceded lands. But beyond mere words, what does it mean to acknowledge Country, to pay attention to the landscape and waterways that crisscross it?

University waterscapes

Wailwan and Kamilaroi descendant Jefa Greenaway, and designer of the New Student Precinct, spent time with Woiwurrung and Boonwurrung language group histories and the University archive in 2019. He found evidence of water on campus:

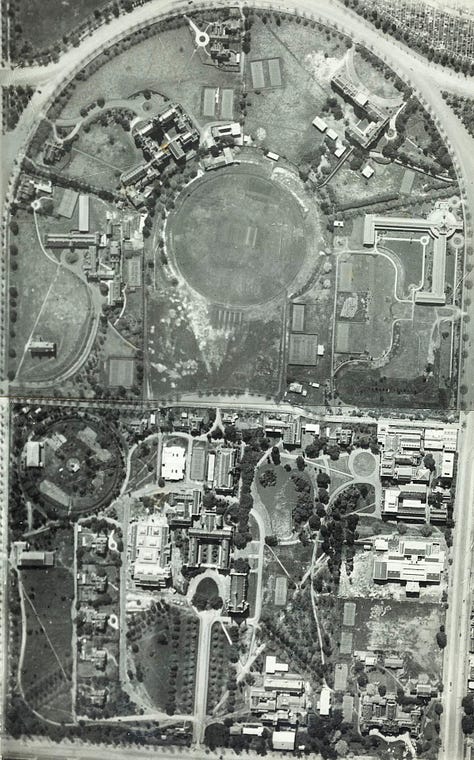

A group of river red gum trees on the northern end of campus, near the cricket ground and residential colleges. These redgums are up to 400 year old, predating the settlement of Melbourne. In the landscape of this continent, when we hear about a red gum, that tells us water used to run through the University.

Maps and photos from early University documents tell us that there used to be a lake or billabong in the middle of campus, where the Concrete Lawn sits today.

And, he found evidence of a creek flowing across campus, from this billabong to Bouverie St – or, as it was known in those early invasion years, Bouverie Creek.

But archival evidence isn’t the whole story.

These waterways have affected the way University infrastructure was built – for example, Old Quad was meant to have been aligned perfectly with a public square on Grattan St, University Square. But the building had to shift to accommodate the swampy marshland surrounding the billabong that fed Bouverie Creek.

When this building was being constructed, workers fought and won one of the first organised labour victories in early colonial Australia. On 21 April 1856 stonemasons in Melbourne downed tools and walked off the job in protest over their employers’ refusal to accept their demands for reduced working hours.

This brought the employers to the negotiating table and led to an agreement whereby stonemasons worked no more than an eight-hour day.

Common nineteenth century workers’ ditty: Eight hours to work, Eight hours to play, Eight hours to sleep, Eight bob a day. A fair day’s work, For a fair day’s pay.

The Living Pavilion

The impression of these waterways continues today. In 2019, an event showcasing and honouring Indigenous knowledge, science, and sustainability took place where we’re standing. This was The Living Pavilion – an immersive public installation curated by Dr Tanja Beer, Barkindji artist and curator Zena Cumpston, and Dr Cathy Oke.

“I see this as a healing space, and it’s a space for reflection,” Zena Cumpston, on-site at The Living Pavilion. For Zena this project represents her love of Country in an urban environment. “I love this space because as an Aboriginal person, I have to go out to the country … to be around the plants that have all these cultural stories that are important to me and tell me about my own people and our knowledges. To have something like this in an urban area, I think, is really special.”

Looking at the photos from the Pavilion, you can see Yorta Yorta and Gunnai artist Dixon Patten’s swirling pathway, using temporary paint to reincarnate the path Bouverie Creek as it once flowed on the grounds of the university, alongside 40,000 Kulin Nation plants. This was a temporary exhibition – but its mark continues today.

Iuk (eels)

In 2021, an article in the Age newspaper reported a strange incident. A group of Melbourne University architecture students, it breathlessly exclaimed, had found a fully grown adult short-finned eel in a tiny pond out the front of the Redmond Barry building. Shocking right? But this didn’t come as a surprise to everybody.

Spread through anecdotal stories and conversations, it is common knowledge for some that an eel migration route still traverses the University of Melbourne campus. Eels – iuk, as they are known in the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung language – are still here.

Where Bouverie Creek once flowed, it has now been replaced by a series of underground drains and stormwater pipes. But the eels follow this ancestral waterway – rearing their heads in some of the ponds and stormwater grates across campus.

Jefa: For me, the metaphor of the eel is quite powerful. It is a story that connects over time and place because what it talks to is the notion of resilience—resilience of Indigenous people, after 240 years, and their commitment to showcasing culture and connecting and maintaining relationships to country.

Across the south-east of the continent, eels follow their ancestral pathways from freshwater streams and lakes out to the sea to spawn in an unknown location in the warm, tropical waters of the Pacific. Down Bouverie Street, gutter grates reveal deep stormwater drains in which eels have been spotted. As we walk today, we will follow the seasonal path of these iuk migrations through the city, towards the Birrarung.

Walk with us down the road, following the map to our next stop at Lincoln Square.

Sources:

Greenaway, Jefa, and Samantha Comte. The Water Story — A conversation between Jefa Greenaway and Samantha Comte. Transcript, July 6, 2019. https://art-museum.unimelb.edu.au/resources/articles/the-water-story-a-conversation-between-jefa-greenaway-and-samantha-comte/.

Hope, Zach. “One Eel of a Story: The Slippery Truth of a Fishy Underground Migration.” The Age, February 6, 2021, 6th February 2021 edition, sec. Victoria. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/one-eel-of-a-story-the-slippery-truth-of-a-fishy-underground-migration-20210122-p56w2z.html.

Kimber, Julie, Peter Love, and Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, eds. The Time of Their Lives: The Eight Hour Day and Working Life. Albert Park, Vic.: Australian Society for the Study of Labour History - Melbourne, 2007.

Thomas, Georgia. “The Living Pavilion Celebrates Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainability.” Green Magazine, May 1, 2019. https://greenmagazine.com.au/the-living-pavilion-indigenous-knowledge-sustainability/.

Images: 1) UniMelb birds-eye photo from 1950s, showing old lake 2) Photo of the lake next to Old Quad, undated 3) The Living Pavilion, 2019

2. Lincoln Square (Ilan)

A Plant Room

Our next stop is not exactly awe-inspiring. We are next to the Lincoln Square Plant Room, part of a flood mitigation and stormwater harvesting infrastructure that stretches across Carlton from the University to Queensberry Street.

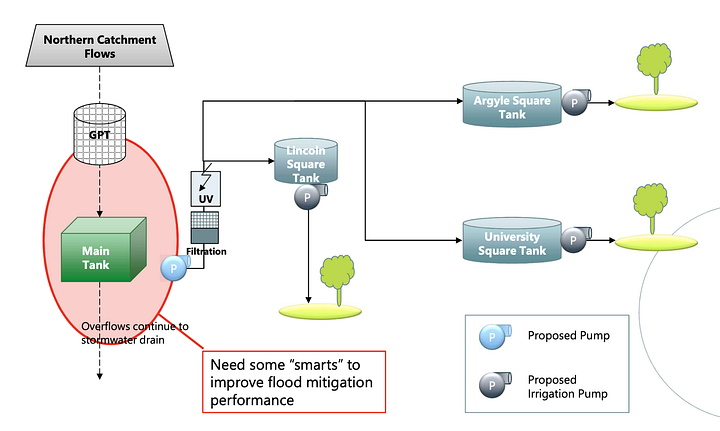

This squat grey structure is the Plant Room, used for the treatment of stormwater prior to delivering to header storage tanks in Argyle, Lincoln and University Squares. In each square, water is filtered into six large underground tanks used to irrigate the grass and gardens around us.

And these are thirsty gardens – the expanded area around Lincoln Square holds 12,897 square meters of irrigation areas, demanding up to 6.97 Megalitres of water per year. That means efficient water use for years of drought.

A Challenge

But the problem is, this area also floods. Quite a lot. Flood mitigation infrastructure requires the reduction of flow of stormwater through the drain system, before it can build up in downstream catchments. The objective of this system is to maximise flood mitigation without significantly compromising Stormwater Harvesting yield (stored in underground tanks, used for Irrigation of Lincoln, Argyle and University Squares).

A Solution

In response, Council developed purge protocols to use up water and create air space in tanks before major storms, predicted according to projected rainfall. The aim is to have full—but not overflowing—tanks after the rain falls.

Scientists and urban planners use a complex series of charts to predict responses to different rainfall events according to their likelihood, runoff volumes, and tank levels.

But they offer a worrying caveat - this is much more effective in storms with less than 50mm rainfall. In high intensity falls (over 8mm/6min) the system starts to back up.

Green spaces, tensions

In a climate changed city, extreme weather events like floods can draw out the tensions between different kinds of infrastructural goals - between flood management and drought management.

When planning for resilient cities, planners are faced with challenges like this: ensuring the collapse of one infrastructure does not require the collapse of another. Or worse, cascading infrastructural failures as flooding leads to power outages.

What gets left behind when we are faced with a disaster? Whose and which needs are prioritised?

Whose knowledge counts in urban design?

But - are technical solutions like water pumps the only way to navigate urban resilience and disaster prevention? Many academics remind us that we should ask not just which knowledge, but whose knowledge counts in planning.

Reflecting on an ongoing project on Indigenous-led approaches to urban water design in Melbourne, Catherine Murphy notes often coming across a ‘lack of knowledge about prior uses of the land before European settlement’.

As we will see in the coming stops, the theft of land and denial of Indigenous knowledge were central to the development of Melbourne as a city. This has implications for today: colonization is not a thing that happened just in the past; its violations and intrusions are embedded in the very cement of our city.

This is why, for Boon Wurrung Elder Na’rweet Aunty Carolyn Briggs AO, another member of the project team, it is about Melburnians - especially urban planners - recognising that much of Melbourne used to be an enormous temperate wetland.

“Country is a living entity. This place is connected to my Country. It’s the biggest wetland in Australia. We have never really unpacked that knowledge. All of those areas have been locked away from us. And now we can start to unpack that knowledge collectively” Aunty Carolyn Briggs

What would our urban design look like if it was informed by the Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung oral histories that we’ve been discussing? Would we design our city differently if we recognised its history as a ‘temperate Kakadu’?

These are the questions confronting urban planners and disaster specialists as we reckon with our past and future.

Sources

Harris, Cecilia. “An Indigenous-Led Approach to Urban Water Design.” Australian Water Association, May 21, 2024. https://www.awa.asn.au/resources/latest-news/community/engagement/indigenous-led-approach-urban-water-design.

Little, Richard G. “Managing the Risk of Cascading Failure in Complex Urban Infrastructures.” In Disrupted Cities. Routledge, 2009.

Moran, Uncle Charles, Uncle Greg Harrington, and Norm Sheehan. “On Country Learning.” Design and Culture, January 2, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17547075.2018.1430996.

Pfleiderer, Ralf. “Flood Purge and SWH at Lincoln Squares Project.” Council Report. Melbourne: Storm Engineering, May 2017.

Images: 1) Stormwater pumping system diagram of Lincoln Square 2) Overview of stormwater storage in southern Carlton

3: Park Hotel (Willow)

Park Hotel Prison

As we reckon with Melbourne’s past, we must confront the more recent history of this area. This stop is a little different two our last two—it is, first and foremost, about people.

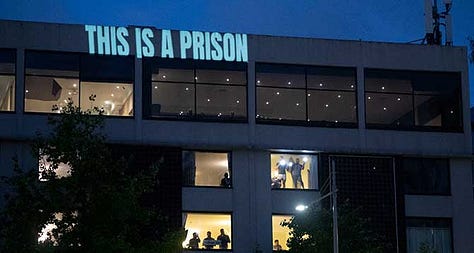

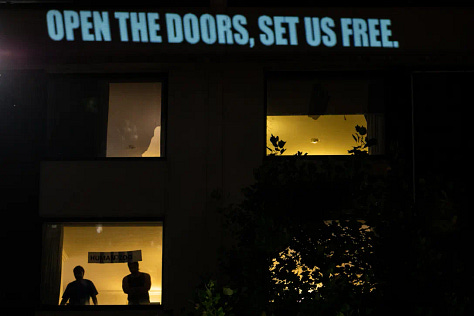

Across the street, the strangely empty and boarded up grey building used to be the Park Hotel. For two years, it held refugees who had been transported from Manus Island, for urgent medical attention on the Australian mainland. It quickly came to be known as Park Hotel Prison.

In April 2022, eight people, the last refugees held at Melbourne’s Park Hotel, were freed. The hotel had been in the news since January, since Serbian tennis champion Novak Djokovic was briefly detained there after refusing to follow COVID vaccine regulations. But for the men inside, Park Hotel Prison had been the only place they knew for two years. Because of successive Liberal and Labour governments’ hardline approach of ‘no asylum seeker arriving by boat will be settled in Australia’, some of these people had been detained in offshore detention and hotels for nine years—with complete uncertainty about when their detention would end.

Park Hotel was not initially advertised as a prison. This mid-range hotel, catering to a business and university clientele, bid for a contract during Melbourne’s exceptional COVID-19 lockdowns. The contract was to keep these refugees in indefinite detention, indoors, with no contact with the outside world beyond a few phone calls, as the pandemic raged on. These people faced an isolation even tougher than the one that all Melburnians had to contend with: no leaving the hotel, no daily walks, and barely any of the mental healthcare that many of them desperately needed.

Linking to vulnerability

Who counts as an urban citizen, especially during disasters? Bolin and Kurtz show us that race, class, and ethnicity determine the experience of disasters for urban residents: differently, and in different ways, according to combinations of these factors. Reflecting on the experience of the Manus Medevac detainees in Park Hotel during COVID, we could add migration status to this list. In fact, migration status, crucially linked to race and class, is a key vulnerabilising factor in the experience of the COVID disaster.

Australia’s borders may seem far from the campus of Melbourne University, or Swanston St, but for two long years, their effects were felt just as keenly here.

For those denied political asylum and citizenship, the pandemic disaster was a vastly different experience to which they were more vulnerable. And for those of us who study at the University, whose classes and offices might be just around the corner from the Park Hotel Prison, how do we respond to an open secret like this? Many academics and university workers joined protests, rallies, and vigils outside the Hotel. Those trapped inside corresponded with friends on the outside to organise interviews and events. At night, words of resistance were projected against the outside of the building. Commuters would join in the morning and evening ritual of ringing their bike bells to signal solidarity with the detainees inside.

Resistance and commemoration

These were efforts, spearheaded by the people inside, to make the invisible visible: to challenge vulnerability.

Combined with media pressure, the spotlight of hosting Djokovic inside the prison, and an upcoming election, these tactics led to the release of the detainees and the decommissioning of the Park Hotel Prison. When planned invisibility fails, different possibilities emerge.

But what of the future of Park Hotel? Will it open its doors once again to an oblivious clientele of travelling workers? Rumours tell of it being sold to another corporation, for unknown purposes. Perhaps more importantly, how do we keep this story alive, the story of a prison in the middle of Carlton? At future stops, we discuss similar challenges.

Now, walk with us as we continue to follow the path of the Bouverie Creek.

Sources

Arroyo, Laura. “Park Hotel Empty as 26 Refugees Are Released, Morrison Government Refuses to Release Remaining 6.” Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (blog), April 7, 2022. https://asrc.org.au/2022/04/07/park-hotel-empty-as-26-refugees-are-released/.

Bolin, Bob, and Liza C. Kurtz. “Race, Class, Ethnicity, and Disaster Vulnerability.” In Handbook of Disaster Research, edited by Havidán Rodríguez, William Donner, and Joseph E. Trainor, 181–203. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63254-4_10.

Australian Associated Press. “Final Detainees at Melbourne’s Park Hotel Freed as Refugee Releases Continue in Lead-up to Election.” The Guardian, April 7, 2022, sec. Australia news. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/apr/07/final-detainees-at-melbournes-park-hotel-freed-as-refugee-releases-continue-in-lead-up-to-election.

Osborne, Zoe. “Beyond the Park Hotel: Australia’s Immigration Detention Network.” Al Jazeera. Accessed May 23, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/13/beyond-the-park-hotel-australias-immigration-detention-network.

Images: 1) Park Hotel prison 2) Park Hotel chalking and activist activity 3) Park Hotel residents behind projections made by friends on the outside

4: University Square (Ilan)

Undergrounding waterways

We’ve now taken a turn down Pelham St, veering off our initial path on Bouverie Street. All available evidence suggests we are still following the path of the creek.

Here, in the rainy months of October and November, Bouverie St and Pelham St pulsate with water during downpours, with much of it flowing through the drains below you. This water is captured by the stormwater pipes we discussed earlier, pumped to the holding tanks at Lincoln, Argyle, and University Squares.

As you walk, pay attention to the deep drains on the southern side of the road, where, if you peek through the grates, you can see metal ladders descending into the dark.

Following streets and their drains does not give us the exact path of pre-urban, pre-colonial creeks — but they can offer our best bet. In reality, creeks wind. They turn through the landscape, following gullies and slopes that are now levelled out with concrete, asphalt, and lawns. But this disappears with the appearance of urban drains.

The undergrounding of rivers and waterways has long been part of the toolkit of urban designers who have converted creeks and tributaries of major urban rivers into drains, culverts, and sewage pipes. In London, efforts have begun to map waterways that once flowed into the Thames, gone since Roman times, with names like Stamford Brook, River Fleet (namesake of Fleet Street), Lamb’s Conduit, and Black Ditch. Online, you can see maps of underground London with sewers, waterways, Tube stations, and even the underground postal route that ferries much of London’s mail.

Later, we’ll discuss the risks of this urbanising strategy and some of its downfalls.

Undergrounding public transit

But creeks aren’t the only underground feature of this area. More recently, you can see construction work for the Melbourne Metro tunnel at the top of University Square.

This new project aims to ferry thousands more commuters through the city, easing the transport bottleneck on the City Loop that most Melbourne residents know too well.

Another case of urban infrastructure risk and reward, the building of the stations for the Metro Tunnel has necessitated the closing of bustling streets and parks through the city, including Grattan Street. As a result, these squares and streets are also being reimagined with new trees, public art, and facilities. A new series of underground tunnels through the city will be reflected by sparkling stations aboveground. And Melbourne will continue to grow. One day, will the underside of our city be as busy as London, with underground tunnels carrying water, waste, and people around the city?

At our next stop, we examine these questions and go deeper into Melbourne’s past.

Sources

Grant, Jill. “The Dark Side of the Grid: Power and Urban Design.” Planning Perspectives, January 1, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665430152469575.

Dangerfield, Andy. “The Lost Rivers That Lie beneath London.” BBC News, October 4, 2015, sec. London. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-29551351.

“University Square – Creating a 21st Century Park - City of Melbourne.” Accessed May 28, 2024. http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/community/parks-open-spaces/park-projects-developments/Pages/reimagining-university-square.aspx.

Images: 1) Underground London map 2) Melbourne metro station artist’s conception

5: Haymarket Roundabout (Willow)

Confluence of Bouverie and Williams Creeks

We stop here at the most likely meeting place of our two waterways: the Bouverie Creek, which we’ve been following, and the Williams Creek—a much bigger waterway. Maps and newspaper gossip are our best indicator that there was a seasonal stream, sometimes even a river, running through here. You can see this in the old maps and sketches attached to this stop on the map – a thin line traces the path of water down the slope, where more detailed sketches show a central gully running to the creek.

To make this guess, we don’t have much to go off. A comment from a nineteenth century local newspaper remarks: “There is a map that shows 'Bouverie Stream' as a tributary of 'River Townsend'. The confluence is near the Haymarket roundabout.” Maps from this time show the two streams meeting in a shallow gully that runs from the top of Elizabeth St down to the mistakenly-described ‘River Yarra’, rightly known as the Birrarung.

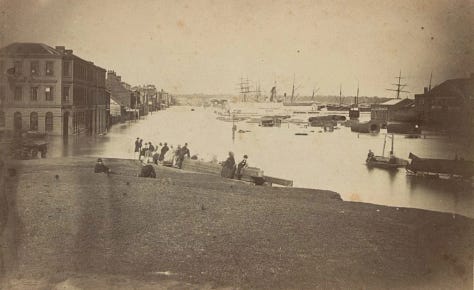

According to reports, in the 1880s Elizabeth Street became one of Melbourne’s first stormwater drains, carrying water from Carlton down to the river. In the Stork Hotel at the top of Elizabeth, an old series of photographs on the wall showed the raising of Elizabeth Street so that what had previously been the street-level bar became the basement.

In fact, Elizabeth St actually used to be one floor lower, and you’ll notice as we travel down the street how many buildings have basements—because these used to be the first floor. The street was filled in and made into an underground drain, placing the creek below ground and many of the shops’ second floor windows at street level. To this day, a friend once told me, many buildings still struggle with rising damp in their basements.

The urban grid as a tool

Why pave over a functional creek? Why put all that effort into turning a gully into a street?

There is a simple answer for this: because it fit the grid. More than many other cities, Melbourne is a grid city. Designed by Robert Hoddle, the Hoddle grid is an almost perfect structure of streets crisscrossing one another and dividing the land into smaller squares. Even our street names hint at this: Lonsdale, Little Lonsdale, Bourke, Little Bourke—or the succession of British monarchs from west to east: King St, William St, Queen St, Elizabeth

In discussions of urban form, many urban planners and designers advocate for the grid as a simple, efficient and useful divider of space. But the grid has a more complicated history. Jill Grant’s historical work with urban grids finds that the grid appears most often in societies which are attempting to centralise or establish power over people and land. In the early settler colony of Australia, the grid was employed to “tame” a wild landscape, to establish military and police control, to prevent large or “unruly” public gatherings by eliminating large open squares, and to enclose land to make it into a commodity.

You’ll notice that Melbourne has few large public squares, often preferring parks or the uneven spaces of Fed Square. This is not unintentional. The Hoddle grid is designed to hide unruly features (like creeks) and prevent unruly gatherings (like protests). It is a technology of anti-conviviality – and one that could, arguably, reduce resilience.

The grid allows for endless expansion – a square can always be extended – oblivious to the existing landscape and culture: it can swallow up creeks, pave over them and turn them into drains, and dispossess people of their land. In their article Placing Property: Theorizing the Urban from Settler Colonial Cities Naama Blatman-Thomas and Libby Porter argue that property is the major tool used to continuously enact dispossession and settlement in Australia. By enclosing land in a series of grids, early colonists made it possible to parcel out the land and sell it at increasingly higher prices. This had the effect of pushing First Nations people off the land despite existing land ownership systems. The response to this, by sovereign Indigenous peoples, informs one of our next stops.

As you walk down Elizabeth St, notice the slope increasing and try to imagine how a creek could have flowed through here. But before that, take the short walk to our next stop.

Sources

Grant, Jill. “The Dark Side of the Grid: Power and Urban Design.” Planning Perspectives, January 1, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665430152469575.

Blatman-Thomas, Naama, and Libby Porter. “Placing Property: Theorizing the Urban from Settler Colonial Cities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43, no. 1 (2019): 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12666.

Rizzetti, Janine. “The Elizabeth Street Creek.” Blog. The Resident Judge of Port Phillip (blog), April 6, 2009. https://residentjudge.com/2009/04/06/the-elizabeth-street-creek/.

Annear, Robyn. Bearbrass: Imagining Early Melbourne. Melbourne: Black Inc., 2014. https://www.blackincbooks.com.au/books/bearbrass.

Images: 1) Elizabeth St gully 2) The Melbourne grid

6: Common Ground, Elizabeth St (Ilan)

Further down Elizabeth St is a unique building in the history of Melbourne’s social services—and a model not many people know about.

Guy: [7:30-7:50] The building’s unusual in the sense of where it's located. It's just on the outskirts of the city, which is the CBD I should say, which introduces some of its own dynamics—the CBD being a bit of a hot spot for chronically homeless people.

This is Elizabeth St Common Ground, a housing-first permanent supportive housing facility for homeless people in near the heart of the city.

At this stop, we’re going to ask you to be considerate of the people whose home you are standing outside. Find a place to stand at a distance from the building, maybe somewhere further down the road, or on the other side of Elizabeth St. Treat this as if it was your house – how would you want people to behave outside of it?

Introducing Common Ground

Common Ground got started in the 2010s, although its inception came about earlier than this. We spoke with Guy Johnson, Professor of Urban Housing and Homelessness at RMIT. He has been involved in the area of precarious housing and homelessness for over 3 decades, as a practitioner and as a researcher, and he has been part of the Common Ground project.

Guy: [0:30-2:00] So if you go back to sort of the late round 2008 the Rudd government came into power and they were very keen—they made homelessness a policy priority, and this was the first time we've sort of seen that at a federal level. So there was a lot of enthusiasm. One of the things that they were sort of pushing for strongly there was new and innovative models, okay. So homeless agencies had evolved a lot since they started in the 1980s and homelessness had changed quite a bit. But there was a particular cohort group of people who are homeless that they were struggling to find sustainable solutions for—and these were often the very chronically homeless, people with drug and alcohol problems, mental health problems, people who had really challenging biographies in the state care system, prison system, and so forth. So you know this really quite small population but incredibly disenfranchised. And a number of people working in America of all places came up with this idea of ‘Housing-First’. So historically what had been going on at that stage was if a person has got a drug and alcohol problem, a mental health problem—treat that and then they'll be able to maintain their housing. Housing-first twisted that all on its head and said “put them in housing, and if they want support or assistance we will provide it, but it's not mandatory”.

Congregate

Common Ground is an example of congregate housing, a model of housing that was popular in the past, but whose popularity is waning.

Guy: [2:03] So Common Ground was a partnership between Grollo Construction, the state government and what was, at that stage, Homeground Services. And it was based on a model that came out in New York, Times Square called Common Ground. Common Ground was different in two ways from just a straight housing-first model: one, it was congregate.

Congregate models involve housing people living with similar challenges, like homelessness, together. At Common Ground there are 120 studio apartments, and people from different backgrounds mix in private and common spaces, with the goal of creating social cohesion. But it hasn’t always been so successful for Common Ground.

Early Challenges

Guy: [4:30-5:10] Common Ground really struggled at the start. There was high turnover, there was the Department of Justice who had nomination rights or access to a number of the units—and they were exiting people directly from prison into Common Ground and the result was the dynamics were pretty volatile for the first year and a half. We did a study that looked at exit patterns, who was leaving and why, and it took a while for that to settle down. And this is not uncommon when you've got a model working with very disadvantaged populations—you've gotta figure out the right mix.

Congregate housing is a model that doesn’t always work. Sometimes, it works as a vulnerabilising factor by compounding stress. This model can compound disadvantage when many people are facing complex challenges in one place. Guy tells us about the difficulties with congregate housing, with conflicts and intimidating environments created by grouping residents with complex trauma, and the need for constant on-site support. He also talks about how no solution is perfect – scattered or individual housing also faces challenges, and they are seeing success here with 70% of the residents at Common Ground staying for two or more years — more housing stability for some than they’ve ever had. But challenges remain.

The Future of Congregate

Guy: [11:08-12:10] It's sort of interesting, I mean there are now Common Ground facilities in every state, so it was certainly popular for a while. What started to happen is what they call fidelity—and that's how closely your model looks compared to the original. Say something is being evaluated, a housing-first programme, and you say we're delivering housing-first. Well: is it housing-first? That's a question of fidelity. Some of the basic principles, in some of the Common Ground models like Tasmania for instance, aren’t congregate living so is that, can we call that a Common Ground model? Probably not. Nonetheless, the whole idea of congregate living was certainly in favour in the 2010s up to sort of 2015. It's fallen a little bit out of favour now, because they had to build it and the construction costs were, you know, significant.

While in the disability sector there has been a process of deinstitutionalisation, in the homelessness sector we’re still building congregate facilities, creating a situation that often compounds social inequality – ‘trans-institutionalisation’ of people with disability. This means that people with complex needs are being grouped together, often not able to get along well, and therefore being unable to stay in these places long-term. Yet people are incredibly resilient – often navigating multiple challenges and far-from-perfect living situations. When thinking about Common Ground, we should think about the resilience of its residents in the face of vulnerabilising forces of homelessness and institutionalisation.

Guy: [12:15-13:00] I think what we're going to see in Victoria—I can't speak for other states—is there will be Common Ground facilities like this one. And out in Dandenong for instance, I've just remembered, but that's for women. But it's a little bit different that one as well, because it doesn't have social mix. It's only for women escaping domestic violence and experiencing some form of homelessness. So you're starting to see that the original model is starting to vary a little bit, based on regional needs and what people can get money for. I think Common Ground will be on our landscape for a long time but I think the central response to rough sleeping and chronic homelessness, and chronically homeless rough sleepers, will more likely be the housing-first which is scattered and uses normal units, in apartment block or houses.

Meanwhile, another dynamic is at play: cost cuts. Successive governments have made endless cuts to public and social housing, leaving programs cancelled or underfunded. Homeless people in our cities are already more vulnerable to disasters, and these cuts are leading them to rely on ever more informal and unstable infrastructures of care. Even with the shift away from congregate housing, Common Ground has made a point.

Guy: [13:03-13:38] And I think what’s driving that is, the evidence is it’s slightly better outcomes, but more I think it’s a question of economics—I think it’s a cheaper model to implement. I may be entirely wrong there, we may see Common Grounds popping up everywhere, but it certainly has as a model really shifted that assumption that homeless people can’t maintain their housing. Common Ground was essential in demonstrating that they can, if given the right housing and the right level of support.

By now, you might be picking up on a particular theme from this tour – or wondering how this relates in any way to underground waterways. As we follow hidden and subterranean histories in the city, natural landscapes and infrastructures are not our only focus.

Our next stop takes us slightly off the path of Elizabeth Street, as we step back in time to the early days of Melbourne’s history—when Williams Creek still flowed openly through the city—and the violence of the frontier was much more present.

Sources

New York City. “Common Ground | Breaking Ground,” 2024.

https://breakingground.org/

.

Power, Emma R, Ilan Wiesel, Emma Mitchell, and Kathleen J Mee. “Shadow Care Infrastructures: Sustaining Life in Post-Welfare Cities.” Progress in Human Geography 46, no. 5 (October 1, 2022): 1165–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325221109837.

Johnson, Guy. Common Ground: Past and Future. Zoom Interview, May 28, 2024.

Launch Housing, “Elizabeth Street Common Ground.” Accessed May 28, 2024. https://www.launchhousing.org.au/service/elizabeth-street-common-ground.

Images: 1) Common Ground external 2) An introduction to Common Ground congregate

7: Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener Memorial (Willow)

Introducing the Frontier Wars

For this stop, we are briefly wandering off the path of the Williams Creek to make a historical detour into the early 1800s.

Joe: [0:48-0:50] I used to think I knew everything about Melbourne history.

This is Joe Toscano, anarchist activist and radio host and one of the members of the Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener Commemoration Committee.

Joe: [14:05-15:15] A potted history of colonisation in Victoria. Manufacturing and the Industrial Revolution led the landed aristocracy of England to send their offspring to Australia, with money and cheap labour, to make a buck.

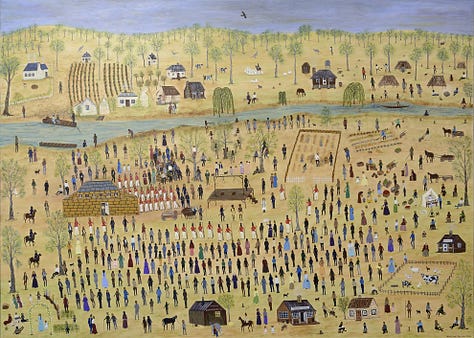

It is 20 January 1842, in the newly-founded colony of Melbourne, and thousands of colonists are gathered in this spot on the edge of town. Although Melbourne was founded only seven years ago, and the small town has barely reached the age of a decade, urban development has been fast and devastating for local ecologies and local Kulin people.

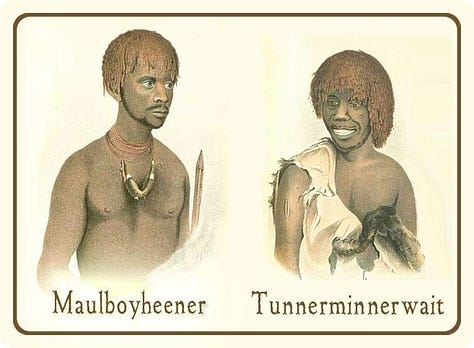

People are gathered to observe Melbourne’s first public execution—the hanging of two Tasmanian Aboriginal men, Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener, who were captured fighting on the colonial frontier east of Melbourne and sentenced for murder.

These two men were part of a group of resistance fighters who fought throughout Victoria, rallying with local groups to push back against the British expansion in the area.

Almost everyone in the young colony had turned out for their execution: soliders leering from the sidelines, shopowners shouting abuse, Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung people silently looking on. The executioner pulls the lever, and Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener, two young men barely over the age of thirty, are killed.

The ‘Friendly Mission’ and Melbourne’s frontier

What happened here? Why were the first public executions in this city Aboriginal men? And how did two young Tasmanian Aboriginal men end up being executed for questionable crimes in Melbourne, hundreds of kilometres from their traditional lands?

To understand this, we need to place it within a broader context of early colonial Australia. This was the time of the Frontier Wars. Historian and broadcaster Boe Spearim, in his regular podcast, speaks about this period lasting from roughly 1788 to the 1930s.

While Melbourne was established in 1835, the invasion of the southeastern corner of the continent, known as the colonies of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land, began much earlier. In Tasmania, decades of fierce and bloody resistance by Tasmanian Aboriginal people had culminated in the last survivors of the brutal Black War putting down their arms. They had been convinced by missionary George Augusts Robinson to move with him to a sanctuary at Wybalenna on Flinders Island in the Bass Strait, with the promise of land and a future return. This never happened. Conditions on the island were cold, windy, and desolate—and by 1840, nearly 100 of the 134 survivors died.

Robinson, on the other hand, was promoted. Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener had joined Robinson on his ‘Friendly Mission’ to recruit the remaining Aboriginal resisters. After their mission was over, and it became clear that only a bleak future awaited on Flinders Island, both men elected to join Robinson at his new post as Protector of Aborigines in the recently-established colony of Victoria .

But there was a conflict going on in Victoria too. Newly displaced groups in the Westernport Bay and Wilson’s Promontory areas east of Melbourne were fighting back against colonists who had set up sheep runs and whaling stations on their land. Robinson arrived in 1839, and Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner left town to join with three Tasmanian Aboriginal women, skirmishing with violent colonists in the eastern districts.

Traumatised by colonial violence and dispossession, the ragtag group of survivors resisted and fought back on land far from home. Retaliation, when it came, was final. After an eight week campaign of resistance, they were captured in November 1841.

They appeared before court on 20 December 1841 in Melbourne, charged with murder. None of the five people charged were allowed to give evidence in court. Despite serious questions about the legal authority of the trial, the Supreme Court found the two men guilty of murder and sentenced them to be hanged. Tunnerminnerwait reportedly said that ‘after his death he would join his father in Van Diemen's Land and hunt kangaroo’.

Together both men were executed for murder on 20 January 1842.

Joe: [12:58-13:40] They were executed because they were involved in armed resistance against the state. So the state was responsible for their execution because they resisted colonisation through armed force. Now most other Aboriginals in Victoria were just killed on the sly – although they were involved in armed resistance — they were killed on the sly. That’s the difference. And that’s why we call it the secret war, the Frontier Wars, and they were quite vicious because within about 15 years of colonisation, 700 squatters owned all of Victoria and the Aboriginal population had been reduced from about 100,000 to about 2,000.

Recognising the Frontier Wars

What kind of disaster was faced by Aboriginal people when Europeans first arrived on Kulin Land? It could easily be argued that our city was a disaster for Aboriginal people living on and around the land that colonists claimed as their own in 1935.

The story of Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener tells us a lot about the Frontier Wars, the trauma of dispossession and attempted genocide, and the foundations of Melbourne. In recent reflections, the City of Melbourne has stated that “their hanging was intended by their judge to communicate a political message to Aboriginal people considering armed resistance to colonisation”. More importantly, it could be considered a war crime.

But despite this and many other examples, it is rarely acknowledged in Australia that British colonisation was violent and Aboriginal people fiercely resisted invasion of their Country. In Melbourne there is very little if any public artwork that references the trauma sustained by Indigenous peoples in the process of colonisation and invasion. By contrast, there are countless memorials to fallen soldiers of other wars far from these shores.

Today, a commemorative memorial, Standing by Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, stands at the intersection of Victoria and Franklin Streets, in front of you.

Joe: [7:00-7:47] Now the interesting thing about the monument is that it’s not a traditional spear-in-the-hand-with-one-foot-on-knee picture. It is a modern monument. It plays with the idea of hanging and a children’s swing. And it also plays with the idea of a coffin, with Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener, with their names on it. And then the story is done in a traditional manner in terms of how it would have been done in their days with the old boxes. So artistically it’s quite an interesting monument. At the same time the native garden was planted, so it’s a place of rest.

Every year on 20th January, a small crowd—much smaller than the original turnout for the execution—comes to pay their respects and remember those who fell in the Frontier Wars.

Joe: [11:35-12:15] Now remember, these were men who were convicted as murderers and hung. 180 plus years later, they are respected members of our community, with a memorial. This is not unusual in human history, people who before their times can be recognised centuries later, and that’s what happened here. But it’s not just that, it’s the simple fact that this occurred. And even now, I don’t believe the Melbourne City Council, which actually own the spot, are doing enough to promote it. But I’m hoping when the railway is completed, there will be thousands of people going past there. And the thing is, we’re very lucky, because this was a little roundabout, and we think it’s the exact spot where they were hung.

This is a space for conviviality, where people can come together to memorialise a rarely-acknowledged history. How often are there monuments or public gatherings for the victims of the Frontier Wars? How do we come together to remember these histories?

Next stop

Joe: [7:50-8:05] So we’re quite disgusted eight years later, because there’s no other monument been created anywhere else in Australia. It’s just extraordinary.

Joe: [8:00-8:20] But what we showed is that radical elements - this is an anarchist organisation, this started off wit the Anarchist Media Institute - radical elements of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community and us, fighting together we could break through the inhibitions which exist.

Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner were buried in an unmarked graves at the Old Melbourne Cemetery which now lies under the Queen Victoria Market, our next stop. Now we head to this final resting place and talk about disaster in Melbourne’s food system.

Sources

Balla, Paola. Executed in Franklin Street - City of Melbourne. November 26, 2015. Art Exhibition. http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/arts-and-culture/city-gallery/exhibition-archive/Pages/executed-in-franklin-street.aspx.

Clements, Nicholas. The Black War: Fear, Sex and Resistance in Tasmania. St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 2014.

Eidelson, Meyer. Melbourne Dreaming: A Guide to the Aboriginal Places of Melbourne. Canberra : Victoria: Aboriginal Studies Press ; Aboriginal Affairs, 1997.

Pybus, Cassandra. Truganini: Journey through the Apocalypse. Sydney, N.S.W: Allen & Unwin, 2020.

Spearim, Boe. “Frontier War Stories.” Frontier War Stories. Accessed March 1, 2022. https://awesomeblack.org/shows/frontier-war-stories/.

Toscano, Joseph. Lest We Forget: The Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener Saga. Melbourne: Anarchist Media Institute, 2008.

Images: 1) Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheer, Frontier Warriors 2) Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, Marlene Gilson (Wadawurrung) 3) Memorial

8: Queen Victoria Market (Ilan)

A graveyard and a market

We are back on Elizabeth St—and on the path of the Williams Creek. Here we are greeted by a familiar sight, the Queen Victoria Market. This market supplies a huge portion of Melbourne’s groceries and food for restaurants, cafes, and delis.

But it is also the resting place of Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener, the frontier warriors we met at the last stop. A little known fact about Queen Victoria Market is that it is also the site of Melbourne’s first major cemetery, old Melbourne Cemetery, which existed in the area from 1837-1922. Today, it is largely located under the market car park.

Joe [

Melbourne’s first cemeteries, one here and the other nearby at Flagstaff Gardens, hold the remains of Wurundjeri and Boonwurrung ancestors, as well as early European colonists. The human remains of an estimated 9,000 people sit as little as 1.5 metres below the carpark.

There have been repeated attempts to redevelop the Market area, ever since the first controversial decision to build the market over the graveyard passed in 1922. At the time, there was a coordinated public opposition led by Isaac Selby, who was a passionate historian of the “founding fathers” of Melbourne. When a Royal Commission allowed the market development, only 1,000 identified bodies were moved to Fawkner Cemetery.

Other groups, especially Indigenous people buried at the site, were given no attention.

In 1999, The Melbourne City Council pledged $800,000 to design a multilevel car park at the market, but ran into obstacles because machine digging is prohibited at gravesites.

More recently, there are plans for a $1.7 billion redevelopment, with high-rise towers, an underground car park and a site called Gurrowa Place. But this project is different.

A deal between the City of Melbourne and LendLease involves a 560-unit apartment tower, a 1,100 bed student accommodation tower, a third tower, and an underground car park. Apparently, the buildings and carpark are planned for outside the boundaries of the Old Melbourne Cemetery, and a “people’s park” is planned inside. But the plan remains contentions—detractors say the risk of any digging, even for a park, is incredibly risky.

And concerns persist related to the scale of the development, its impact on the spirit of the market, and whether LendLease can actually deliver on its promises of sensitivity.

Melbourne’s food system

Meanwhile, Queen Victoria Market is still one of the most important markets in the city.

In times of disaster, food hubs are often the first to be impacted, compounding disaster vulnerability and risk for urban residents. Exactly this happened during COVID.

Gyorgy: [1:00-1:35] Well there were a number of ways in which the COVID pandemic impacted peoples’ ability to source food, which was really obvious at the time. One was that it highlighted how narrow our options had become, how really concentrated our supply chains had become, and particularly our dependence on supermarkets. And it’s not just that we shop at supermarkets, it’s that supermarkets also control so much of the food supply and the supply chains. And we’re at the real bottleneck there—particularly when there is a run on supermarkets.

This is Dr Gyorgy Scrinis, a nutrition expert and Associate Professor of Food Politics and Policy at the University of Melbourne. He spoke to us about Queen Vic during COVID.

Gyorgy: [1:43-2:32] But places like the Vic Market were so precious at the time, because it remained open, and a place to get fresh fruit and veg—and everyone was really looking for those fresh foods at the time, not just relying on packaged foods. And during the lockdowns, the distance we could travel was really restricted, and that really would have impacted many people who were living far away from grocery stores and even supermarkets. So for anyone living close by to the Vic Market, especially in the city area, it would have been a really precious resource. I know myself, I was living probably just outside the 5km zone of the Vic Market, but I would push the boundaries a bit and trek down to the Vic Market.

Student food security, in particular, was affected by the changes wrought by lockdowns.

Gyorgy: [3:25-4:03] So this a really, quite a significant impact and we had just started researching university student food insecurity just before COVID hit. Because it’s actually been a longstanding problem, university students being food insecure, and it’s probably been a growing problem. But very much a hidden problem. In the sense that the universities themselves barely recognised the issue, student unions often had free breakfast programs to meet the needs of their food insecure students, but otherwise it wasn’t much talked about nor researched—even the extent of it wasn’t well known.

Gyorgy: [4:39-5:18] So in terms of food insecurity, it really hit those international students most. Much more so than domestic students—that was really evident. And many had to turn to food relief agencies, either outside the University but also at the University itself. Melbourne University recognised it had a very problem early on, and quickly pivoted and started sourcing frozen meals from SecondBite organisation to give to students. And that was a really welcome program at the time—and international students in particular were really relying on that.

According to Gyorgy, what the pandemic did was uncover hidden problems—something a lot of disasters tend to do. And this has had lasting impacts.

Gyorgy: [5:19-5:37] And what it did, what this pandemic did, is actually expose this very longstanding problem of university student food insecurity—it exacerbated it for some, but it just brought it out into the open. So suddenly the University had to acknowledge a problem it either wasn’t aware of or didn’t want to acknowledge previously.

Gyorgy: [7:36-8:12] And coming out of COVID, we’ve gone into the inflationary period and the cost of living crisis. And once again, so many people are impacted now—in fact, a much wider portion of the population. And this goes way beyond what happened during COVID. And, so the government itself is having to acknowledge and address this whole problem of cost of living and we see that the food banks and the food pantries, the food charities around Australia, just are at capacity and demand is continuing to grow.

Gyorgy: [9:15-9:30] But also what this whole food bank and food charity industry is doing is actually supporting the existing dominant, and very corporately controlled food system that we have. And not actually challenging it in any way.

Gyorgy: [8:40-8:50] It gets to a point where you can no longer think it’s a small issue that can just be addressed by a few charities.

So if food banks are only a band-aid solution, what have we learnt from COVID?

Gyorgy: [2:33-2:58] People started to explore other ways of sourcing food more directly from farmers and all sorts of experiments in growing food your own food as well. It really showed the lack of resilience of our food system. And at least, for many people, it opened their eyes to the vulnerabilities of these very concentrated supply chains.

Bushfires, floods, pandemics and climate change demonstrate just how important a healthy food system is for disaster resilience.

To do this, we need to move away from supermarket-run supply chains—and toward those experiments that Gyorgy talked about.

Next stop

Now, we hop on the tram and spot some key sites as we follow the path of the Williams.

Sources

Cole, Colin E. Melbourne Markets, 1841-1979 : The Story of the Fruit and Vegetable Markets in the City of Melbourne / Edited by Colin E. Cole. Footscray, Vic: Melbourne Wholesale Fruit and Vegetable Market Trust, 1980.

Morgan, Marjorie Jean. The Old Melbourne Cemetery, 1837-1922. Australian Institute of Genealogical Studies, 1982.

Murphy, Maureen, Rachel Carey, and Leila Alexandra. “The Resilience of Melbourne’s Food System to Climate and Pandemic Shocks.” University of Melbourne, 2022. https://doi.org/10.46580/124370.

Scrinis, Gyorgy. Queen Vic Market & Melbourne’s Food Security. Zoom Interview, May 22, 2024.

Razak, Ishkhandar. “Every Day, Thousands of People Walk over a Burial Ground at One of Melbourne’s Biggest Tourist Attractions.” ABC News, July 23, 2023. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-07-24/queen-vic-market-cemetery-burial-ground-development-lendlease/102624880.

Swift, Neil., and Edmund Finn, eds. The Chronicles of Early Melbourne 1835-1852, Historical, Anecdotal and Personal, by “Garryowen.” Melbourne: Fregusson and Mitchell, 1964.

Images: 1) Old Melbourne Cemetery 2) Queen Vic redevelopment

9: Williams Creek Crossing (Willow, 5 mins)

Redgums

Back in 1838, this street—Elizabeth Street—was less a street and more of a gully. Glorious one day, it could be a flooded hellhole the next. The people of early Melbourne had other names for this riotous waterway—“a jungly chasm” is particularly evocative.

In his Chronicles of Early Melbourne, journalist Edmund Finn, aka Garryowen, counts as many as six floods within the first ten years of settlement, as well as a snow storm. As early as 1835, the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung peoples tried to warn settlers about the dangers of building a city on a floodplain. Nobody listened.

And a familiar weather pattern set in:

“During the first three weeks of December in 1839, the weather was scorching, and hot-windy. When a sudden change set in, and for three days and nights there was a continuous downpour of rain.” writes journalist Garryowen